Under the reign of Emperor Rudolf II, who ruled from 1576 to 1612, Prague had become one of the most important cultural and scientific centres in Europe of the period. As an avid lover of the arts and sciences, the emperor surrounded himself with artists, men of letters and scientists that, under his protection, were able to experiment and conduct research in all the spheres of human knowledge, often attaining important and exceptional results. Among the numerous men who served the king from all over the kingdom and the lands beyond its borders, there were a few of them whose genius and achievements have made them immortal and famous to this day. Among those who deserve a special place in history there is surely the astrologer, astronomer and alchemist Tycho Brahe.

Under the reign of Emperor Rudolf II, who ruled from 1576 to 1612, Prague had become one of the most important cultural and scientific centres in Europe of the period. As an avid lover of the arts and sciences, the emperor surrounded himself with artists, men of letters and scientists that, under his protection, were able to experiment and conduct research in all the spheres of human knowledge, often attaining important and exceptional results. Among the numerous men who served the king from all over the kingdom and the lands beyond its borders, there were a few of them whose genius and achievements have made them immortal and famous to this day. Among those who deserve a special place in history there is surely the astrologer, astronomer and alchemist Tycho Brahe.

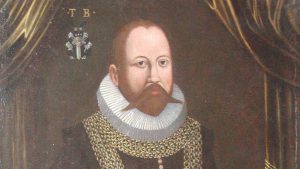

Born into an aristocratic family in Knutstorp, Denmark on December 14, 1546, Tyge Ottesen Brahe – this is his full name – received an early education at his uncle’s house and at the age of seven already had a good knowledge of Latin and a basic knowledge of mathematics. It was during the lunar eclipse of August 21, 1560 – when he was not yet fourteen years old, but already an expert in astronomy – that the young Brahe decided to dedicate his life to the observation of the night sky. He studied rhetoric and philosophy in Copenhagen and then, in Leipzig and Wittenberg, he took up astronomy, law and mathematics, achieving outstanding results for a young man of his age. Through his studies, he aimed to reconcile the geocentric Ptolemaic system with the new heliocentric vision of Copernicus, by elaborating his own special and original vision of the cosmos.

On 11 November, 1572, he observed the explosion of a supernova in the constellation of Cassiopeia. He  described the event a year later in his work De stella nova, which brought him considerable fame because it gave a decisive blow to the Aristotelian-Ptolemaic conception of the universe that considered the stars and planets as immutable and fixed bodies. He travelled widely throughout Europe and became the astronomer of the Danish King Frederick II, who allowed him to set up a sky observation laboratory, which was quite an achievement for the time and that was built on the island of Hven, between Denmark and Sweden, where Brahe worked for over twenty years. But on the death of Frederick, he was obliged to leave his golden kingdom and the large amount of wealth he had accumulated, because of incompatibilities with the new sovereign and sought refuge in Prague at the court of Rudolf II of Hapsburg. When he arrived there in 1599, he was already famous and known to the Emperor, who considered him the best scientist of his time. When he arrived in town, Rudolf asked to meet him alone in the parlour. They say that when the Emperor saw him, he came down from the throne and shook hands with him: an honour conferred only to a sovereign.

described the event a year later in his work De stella nova, which brought him considerable fame because it gave a decisive blow to the Aristotelian-Ptolemaic conception of the universe that considered the stars and planets as immutable and fixed bodies. He travelled widely throughout Europe and became the astronomer of the Danish King Frederick II, who allowed him to set up a sky observation laboratory, which was quite an achievement for the time and that was built on the island of Hven, between Denmark and Sweden, where Brahe worked for over twenty years. But on the death of Frederick, he was obliged to leave his golden kingdom and the large amount of wealth he had accumulated, because of incompatibilities with the new sovereign and sought refuge in Prague at the court of Rudolf II of Hapsburg. When he arrived there in 1599, he was already famous and known to the Emperor, who considered him the best scientist of his time. When he arrived in town, Rudolf asked to meet him alone in the parlour. They say that when the Emperor saw him, he came down from the throne and shook hands with him: an honour conferred only to a sovereign.

Rudolf II immediately appointed him astronomer and astrologer of the court and offered him as a dwelling the Castle of Benátky nad Jizerou. But Brahe also became an intimate and sincere friend of the Emperor. In Prague, he continued his studies also in medicine and alchemy and always had a great influence on the Emperor, who often called him for advice and astrological consultations, to such an extent that he soon aroused great envy among his colleagues, that earned the Danish scientist the nickname of “evil spirit of the emperor”. Brahe advised Rudolf not to marry, because children –he argued – would have caused misfortunes. The king followed his advice, much to the disappointment of his family and the Vatican. The scientist’s alchemist skills are also witnessed in various episodes. When he was a young man, following a dispute over a mathematical formula, he lost his nasal septum and had to make a gold and copper prosthesis, himself, which he attached to his face with a mysterious adhesive ointment of his own making. He created alloys and precious stones, but never revealed his findings in this field, because he feared they would fall into the wrong hands. He was a staunch Lutheran, but this did not prevent him from being very superstitious. He always carried amulets and talismans to evoke good fortune and even believed the celestial bodies had an influence on the Earth and humans. However, he supported the idea that human freedom was able to release the individual from celestial influences: “Astra inclinant, non determinant”. He produced astronomical instruments for Rudolf II, which were among the most advanced for that period, and he made major observational studies on the moon and comets that revolutionized the scientific conceptions of that period.

Rudolf II immediately appointed him astronomer and astrologer of the court and offered him as a dwelling the Castle of Benátky nad Jizerou. But Brahe also became an intimate and sincere friend of the Emperor. In Prague, he continued his studies also in medicine and alchemy and always had a great influence on the Emperor, who often called him for advice and astrological consultations, to such an extent that he soon aroused great envy among his colleagues, that earned the Danish scientist the nickname of “evil spirit of the emperor”. Brahe advised Rudolf not to marry, because children –he argued – would have caused misfortunes. The king followed his advice, much to the disappointment of his family and the Vatican. The scientist’s alchemist skills are also witnessed in various episodes. When he was a young man, following a dispute over a mathematical formula, he lost his nasal septum and had to make a gold and copper prosthesis, himself, which he attached to his face with a mysterious adhesive ointment of his own making. He created alloys and precious stones, but never revealed his findings in this field, because he feared they would fall into the wrong hands. He was a staunch Lutheran, but this did not prevent him from being very superstitious. He always carried amulets and talismans to evoke good fortune and even believed the celestial bodies had an influence on the Earth and humans. However, he supported the idea that human freedom was able to release the individual from celestial influences: “Astra inclinant, non determinant”. He produced astronomical instruments for Rudolf II, which were among the most advanced for that period, and he made major observational studies on the moon and comets that revolutionized the scientific conceptions of that period.

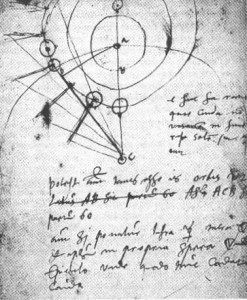

In 1600, a young and promising scientist arrived in Prague, invited by the Emperor to act as an assistant to  the great Brahe. The young man and the master began working together despite their conflicting ideas. But their characters compensated each other and Rudolf’s idea of putting them together gave a great contribution to astronomy and science in general. The young assistant was called Johannes von Kepler and because of Brahe’s observations on the position of Mars, he was able years later to formulate his famous laws on planetary motion.

the great Brahe. The young man and the master began working together despite their conflicting ideas. But their characters compensated each other and Rudolf’s idea of putting them together gave a great contribution to astronomy and science in general. The young assistant was called Johannes von Kepler and because of Brahe’s observations on the position of Mars, he was able years later to formulate his famous laws on planetary motion.

Brahe created an original cosmological theory, according to which even if the Earth was supposedly at the centre of the universe, only the Moon and the Sun went around it. The other planets, instead, rotated around the sun. In the Benátky nad Jizerou Observatory, Brahe and Kepler were able to revolutionize astronomy by working together until the old master’s death on October 24, 1601.

A lot has been said and written about Brahe’s death and various theories have been put forward, some of which also quite imaginative, such as the one where is supposed to have died because his bladder had burst, because he did not want to leave the table to go to the toilette during a banquet, so as not to be disrespectful to the Emperor. According to some, the scientist died from mercury poisoning during one of his alchemic experiments; according to other she became ill after a banquet and died because of kidney failure; but there are also those who believe he was murdered. In November 2010, a Czech-Danish team opened his tomb to examine his remains. In the samples, traces of mercury were found, but not in such high concentrations as to determine the death of the astronomer. However, the exact circumstances of the death of this great scientist have never really been clarified and the cause still remains a mystery after over 400 years.

A lot has been said and written about Brahe’s death and various theories have been put forward, some of which also quite imaginative, such as the one where is supposed to have died because his bladder had burst, because he did not want to leave the table to go to the toilette during a banquet, so as not to be disrespectful to the Emperor. According to some, the scientist died from mercury poisoning during one of his alchemic experiments; according to other she became ill after a banquet and died because of kidney failure; but there are also those who believe he was murdered. In November 2010, a Czech-Danish team opened his tomb to examine his remains. In the samples, traces of mercury were found, but not in such high concentrations as to determine the death of the astronomer. However, the exact circumstances of the death of this great scientist have never really been clarified and the cause still remains a mystery after over 400 years.

Before he died, Braheis believed to have repeated several times the phrase: “Ne frustra vixisse videar” (May I not seem to have lived in vain). On his death, Rudolf II, saddened by the event, had him buried with great pomp, in the church of Our Lady of Týn, giving orders that a life-size monument be erected in the church to his memory. The following words were inscribed on his tombstone: “Neither power nor wealth, only Art and Science will endure”.

by Mauro Ruggiero

Original version: